How I am trying to discover the drivers of a form of liver cancer in children

Liver cancer in children is thankfully rare and when it does happen it most often develops out of a (relatively) normal liver (i.e. not cirrhotic or scarred) – this is most often a ‘hepatoblastoma’. These tumours are often curable thanks to our amazing oncologists and surgeons.

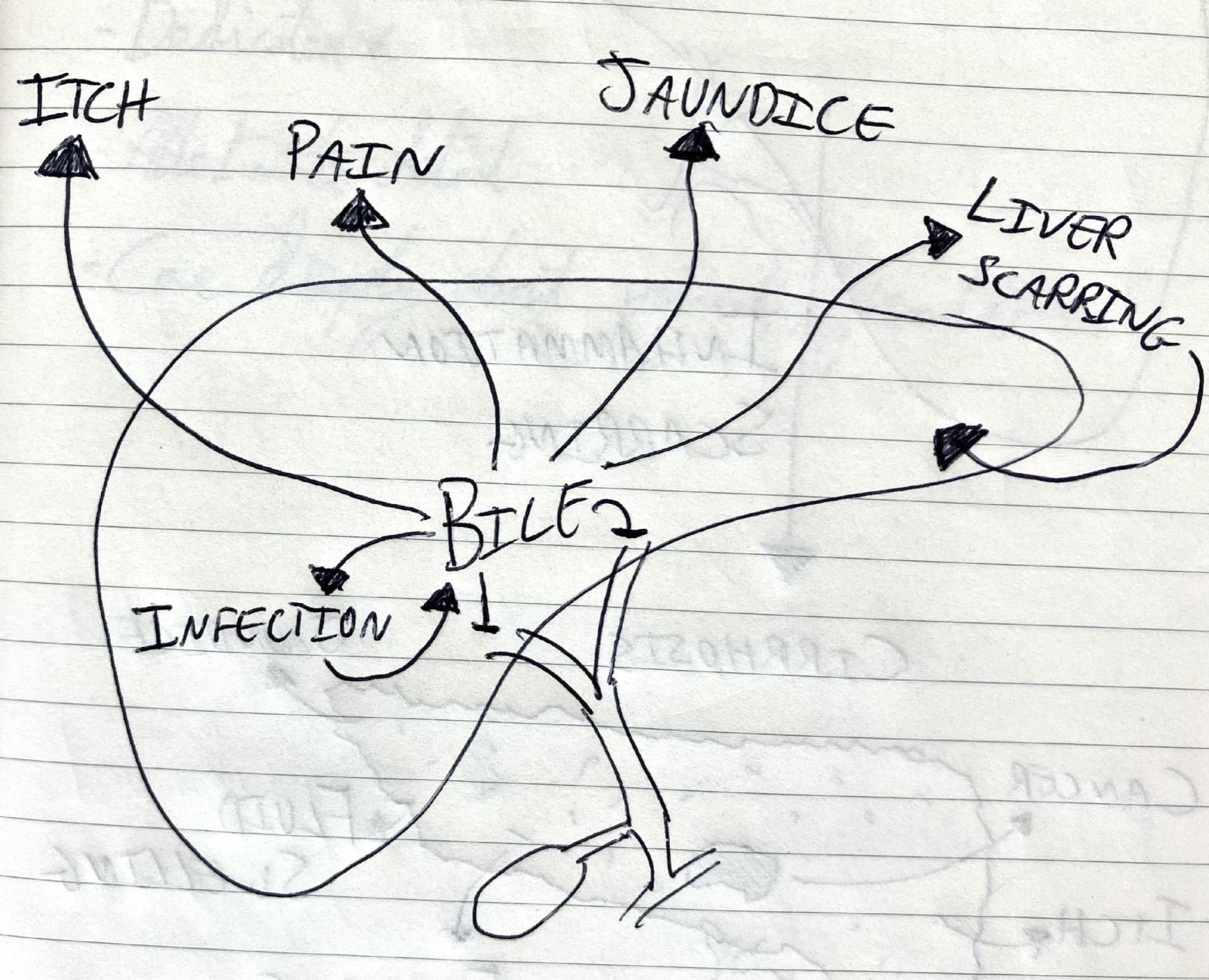

In contrast, liver cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer-related death in adults worldwide. It usually develops on a background of cirrhosis (end stage liver scarring) after many years and is typically called ‘hepatocellular carcinoma’ (or ‘HCC’). Children can get HCC but it is rare and often the only treatment is a liver transplant. There are some liver conditions that have a particularly high risk of HCC in childhood (e.g. ‘BSEP deficiency’) and others that have a low risk of HCC (e.g. biliary atresia).

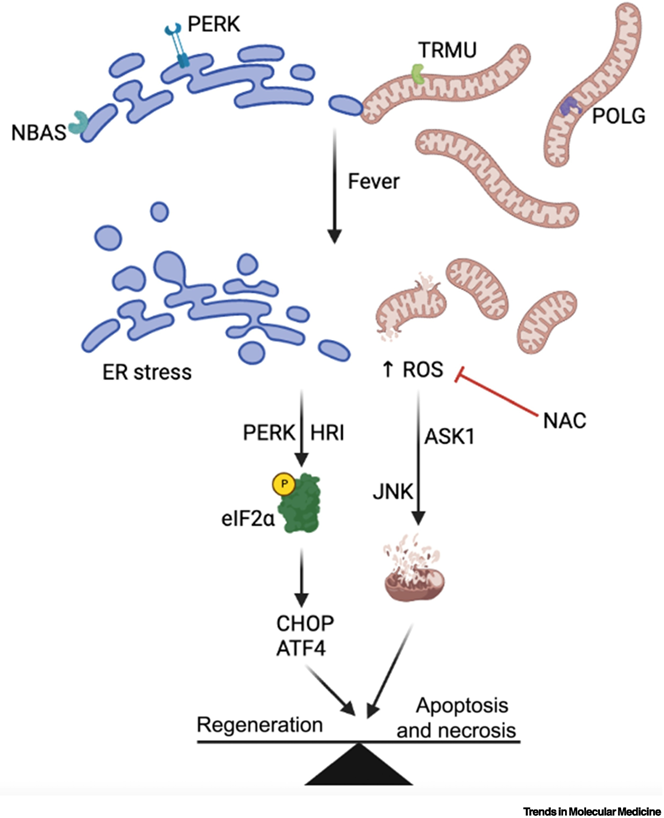

I want to discover why children with BSEP deficiency get HCC whilst children with biliary atresia do not, despite them having the same degree of liver scarring. Could it be to do with the inflammation around the tumour?

A small group of us from across Europe have been generously funded The Little Princess Trust and the Children’s & young people’s Cancer Association (CCLG) to study this. We are tackling this by using a cutting-edge spatial transcriptomics technique called VisiumHD in collaboration with the University of Edinburgh.

First, this involves very carefully selecting the right tissue. This shows a liver tumour arising on the background of cirrhosis.

Then you identify a key region within it to perform the spatial transcriptomics.

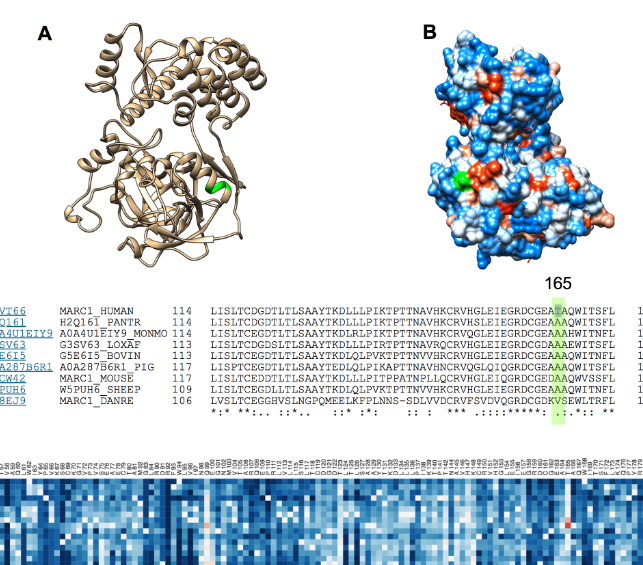

Next, we performed a very careful set of steps to generate the data. And subsequently, with a lot of help from a bioinformatics expert at University of Edinburgh, we can label small regions (8 micron squares) with their gene signatures.

This is a ‘noisey’ preliminary data image before it has been cleaned up, including some non-specific signals (especially the orange smudge at the bottom right). However, the tumour cells (yellow, top right) stand out different to the background liver cells (blue), and scar cells (green).

The analysis is still on going and it will need a lot of follow-on experiments to understand the results.

I’m hopeful that I’ll be able to share the full story of what I’ve discovered in the next year or so. In the meantime, please get in touch if you’d like to discuss VisiumHD or single-cell spatial transcriptomics. I’m always eager to collaborate with new people, and there are opportunities to join me here in Birmingham.