A pivot in my research field

Up to this point

Bile duct diseases are serious conditions with few treatments. They are the liver conditions most in need of further research. And for those who know me, it will be seen as a ‘side step’ away from my previous topics..

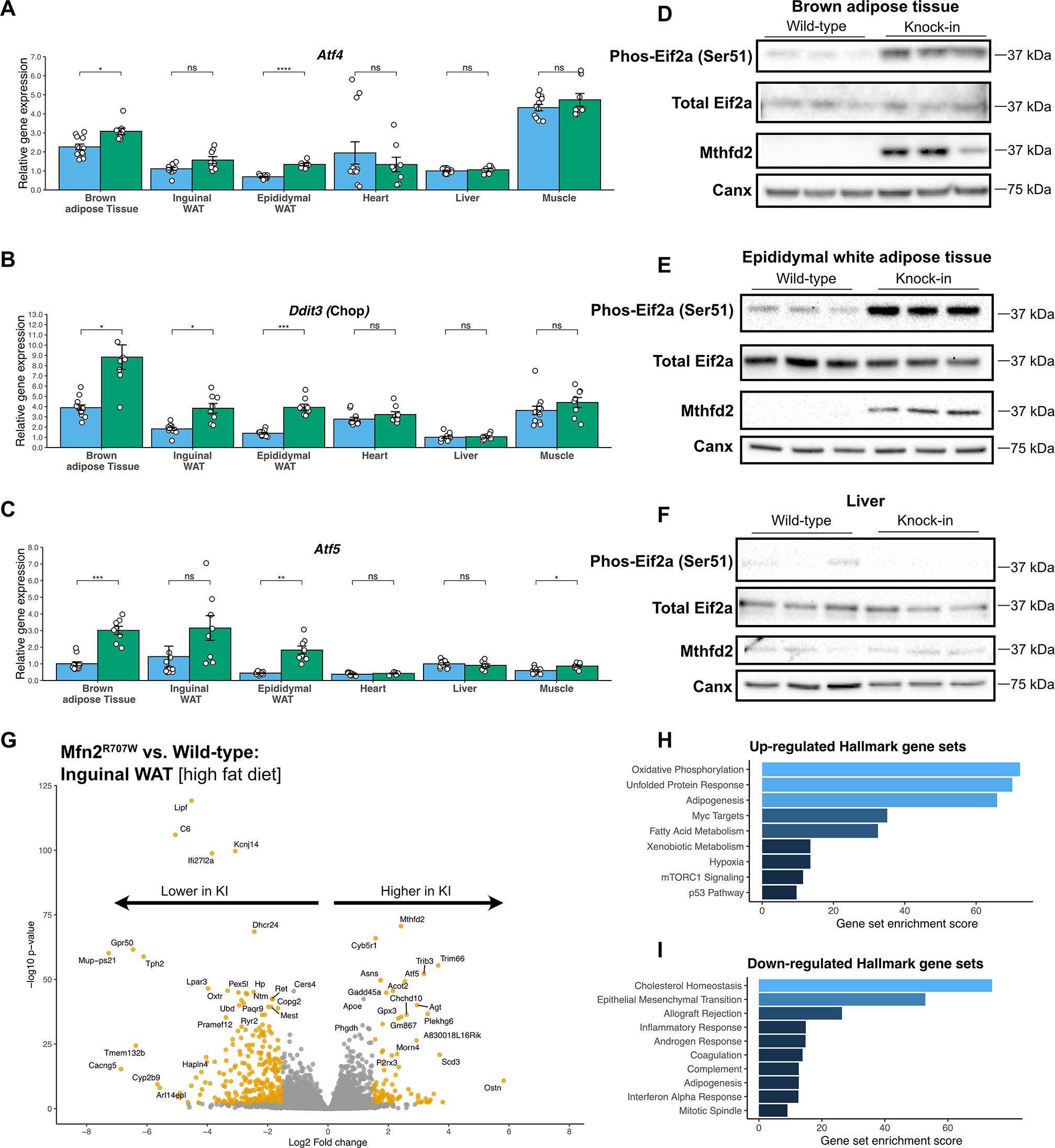

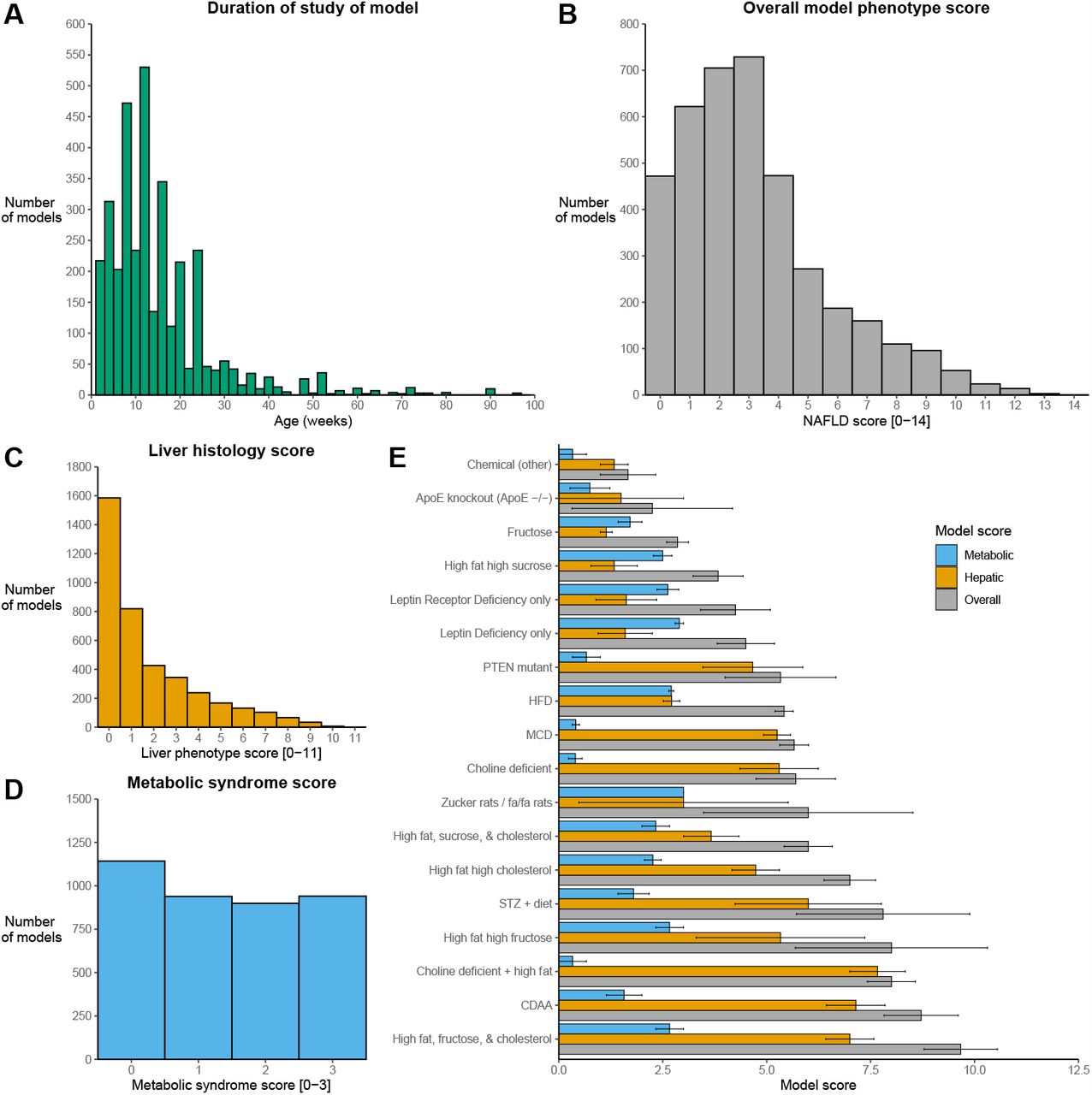

I have been interested in liver disease since the first year of medical school. Subsequently, I decided to focus on genetic conditions that are linked to the build of fat in the liver. This has been my field of research for the last eight years.

About bile duct diseases

Since moving (back) to Birmingham, it is clear that biliary disorders are the most in-need conditions. This includes diseases where: the large tubes that drain bile out of the liver become scarred so permanently close up (e.g. ‘biliary atresia’), and diseases that affect the microscopic bile ducts inside the liver (e.g. primary biliary cholangitis). There are some conditions that can affect both big and small bile ducts (e.g. primary sclerosing cholangitis).

Diseases of the bile ducts are horrible conditions. When bile doesn’t drain out of the liver (into the intestine), it builds up and goes back into the blood. This causes itch, jaundice (skin & eyes looking yellow-green), and (sometimes life-threatening) infections. All these conditions also cause severe fatigue, even if the liver itself is still working.

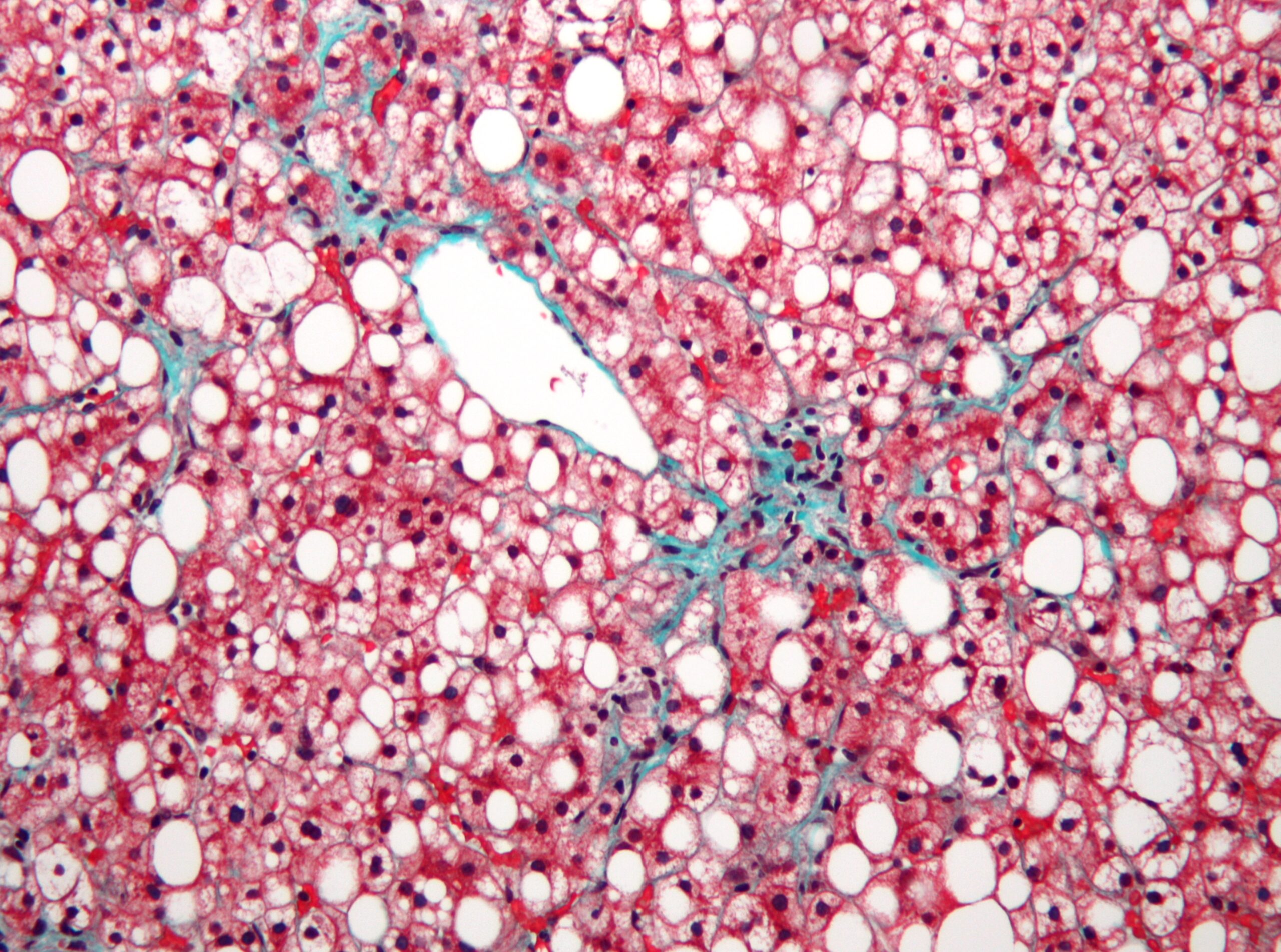

Liver inflammation, scarring, and its effects

Bile duct diseases are caused by inflammation. Exactly what triggers the inflammation isn’t completely known. In addition, the blocked bile ducts makes the inflammation worse. Over time (months to years, depending on the condition) this inflammation results in scarring of the liver: replacing the healthy working liver cells with scar tissue. This is called ‘cirrhosis’ in its most severe form. The effect is two main groups of problems: (1) it slows the flow of blood into the liver (‘portal hypertension’), and (2) the liver can’t do its normal jobs (‘liver failure’). In portal hypertension (1) there is build up of pressure in the veins in the intestines, which causes fluid to accumulate in the abdomen (‘ascites’) and risk of bleeding into the stomach. The liver normally gets rid of toxins our body makes all the time, so when this doesn’t happen (2) patients can become more muddled (‘encephalopathy’). In addition, adults lose muscle and children don’t grow as they normally should. The fatigue and effect on quality of life can be profound. These symptoms can happen with any cause of long-term liver disease, in their most severe forms.

So, there is a general process of bile ducts → inflammation → liver scarring (‘biliary fibrosis’), despite having lots of different causes. I want to contribute to our understanding of this process and see how true my findings are across several diseases, including biliary atresia and primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Biliary atresia: a bile duct disease affecting babies

Biliary atresia is rare (about 60-70 cases per year in the UK) and important. It accounts for about two thirds of all liver transplants for children; and around three quarters of all patients with biliary atresia will need a liver transplant at some point in their lives. In the first few weeks after birth, babies with biliary atresia become jaundiced and their poo goes pale because the bile ducts shrivel up and become blocked. The treatment is an operation (the ‘Kasai’) to allow bile to drain out the liver by joining intestine to where the bile ducts should be. This operation works well for some children whilst for others need a liver transplant whilst still under a year old. With treatment (including liver transplant), more than 95 out of 100 children with biliary atresia survive, but without treatment it would be fatal. The Children’s Liver Disease Foundation is a good source of information on biliary atresia.

The cause of biliary atresia isn’t known and there aren’t any drugs that stop the liver inflammation or scarring. Patients with biliary atresia (or its complications) make up the vast majority of (particularly in-patient) workload for children’s liver departments. So, I think it is the most important condition to be researching in my field. (This is also consistent with taking an effective altruism approach to research, within my clinical niche.)

Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a bile duct disease affecting older children & adults

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is another condition that affects the liver’s bile ducts and it is in need of research. It affects about 10,000 people in the UK. Around half will need a liver transplant at some point in their lives. Patients with PSC get inflammation and scarring of their bile ducts: big (outside the liver, like biliary atresia) and/or small (microscopic & inside the liver). It affects both adults and children, particularly those who have inflammatory bowel disease (‘IBD’). A problem with PSC may become known because they get infections in bile ducts, jaundice, pain around the liver, or high liver blood tests when checked for IBD. The severity is variable: some people will need a liver transplant whilst others will have minimal symptoms. We don’t have any medicines that stop the inflammation or scarring, just like for biliary atresia. We also aren’t sure what the exact trigger is for the bile duct damage, again like biliary atresia. So, I consider PSC one of the highest priorities for research given the need for transplant, unpleasant symptoms, and lack of treatment. PSC Support is a great source of information about PSC.

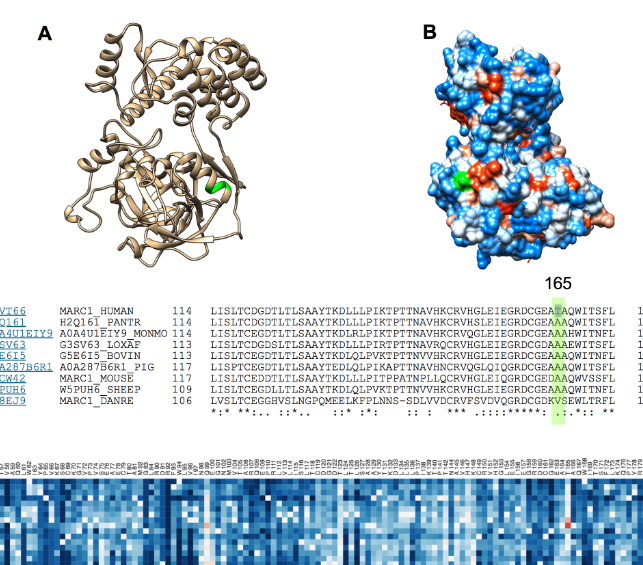

I see similarities between biliary atresia, PSC, and other conditions that injure the bile ducts. My current plan is to study (a) scar-forming cells around the bile ducts, and (b) a group of proteins/chemicals on bile duct cells that are important for inflammation/scarring. I hope that what we find will ultimately contribute to improving the lives for people with these conditions.