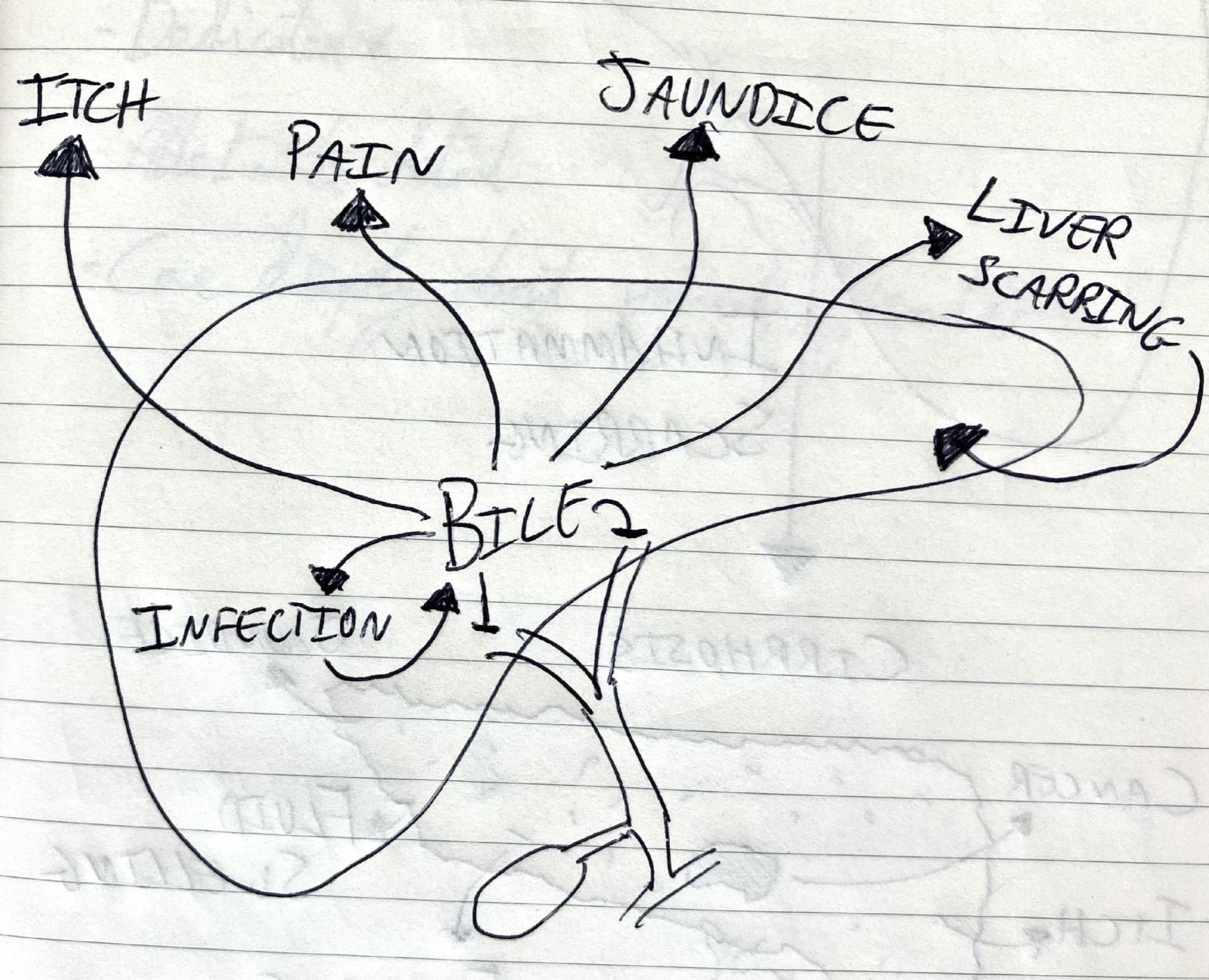

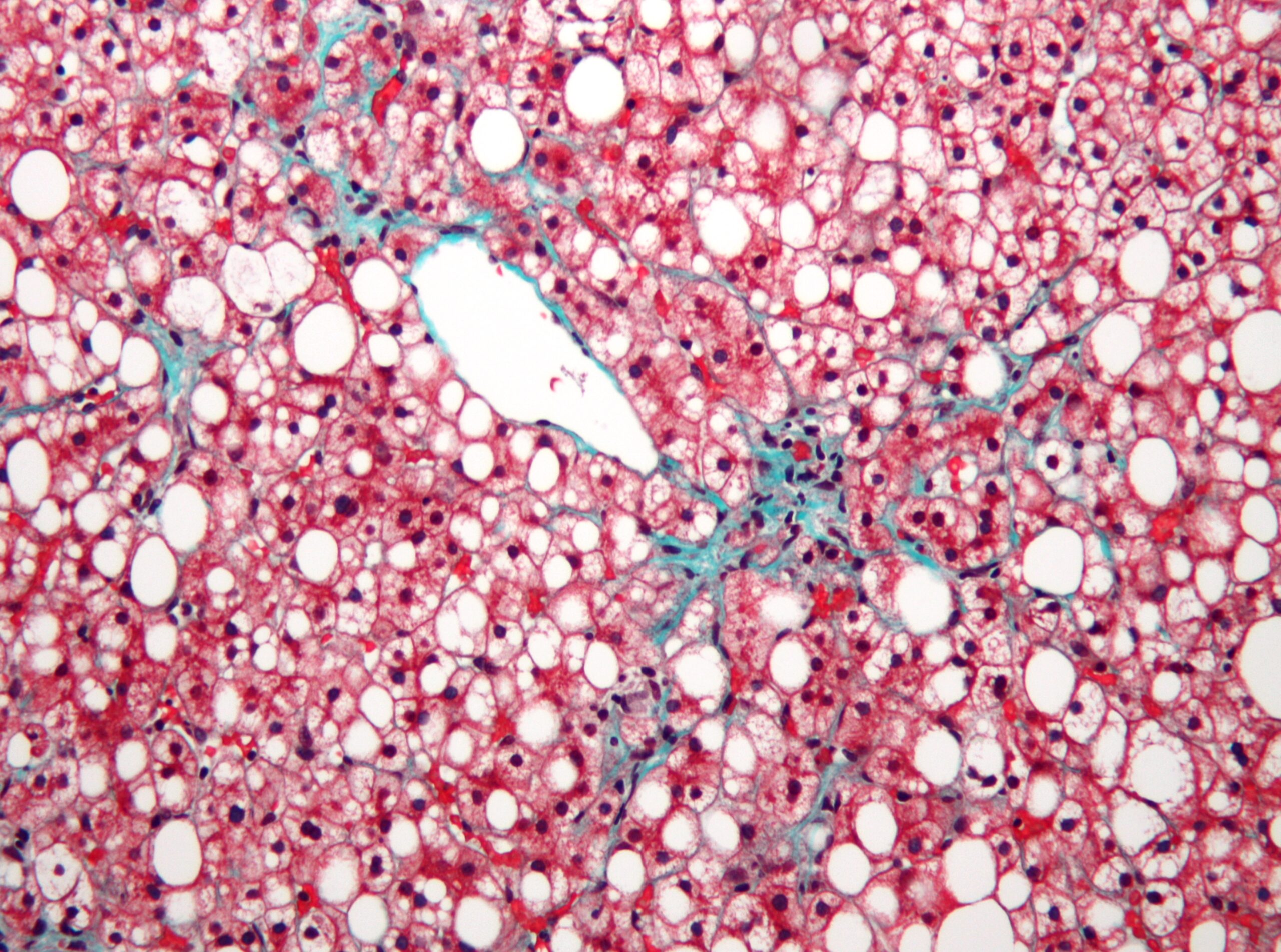

Most of my research has been to understand a problem that affects up to 20% of all children. ‘Hepatic steatosis’, ‘non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)’, or just ‘fatty liver’ is the accumulation of excess fat inside liver cells. It is closely linked to obesity. So as more children (& adults) have become overweight in the last 50 years, more people have got fatty liver. For most people, fatty liver isn’t too harmful, but for some it will cause inflammation and scarring. This can lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer, just like excessive alcohol can. This process usually takes 20-30 years. However, fatty liver is strongly linked to diabetes and heart disease. So, the main cause of illness (& death) for people with fatty liver is heart disease, not liver disease.

I have lead research in three main areas of fatty liver disease:

- Describing the differences between children and adults with fatty liver

- Understanding the genetic causes of fatty liver

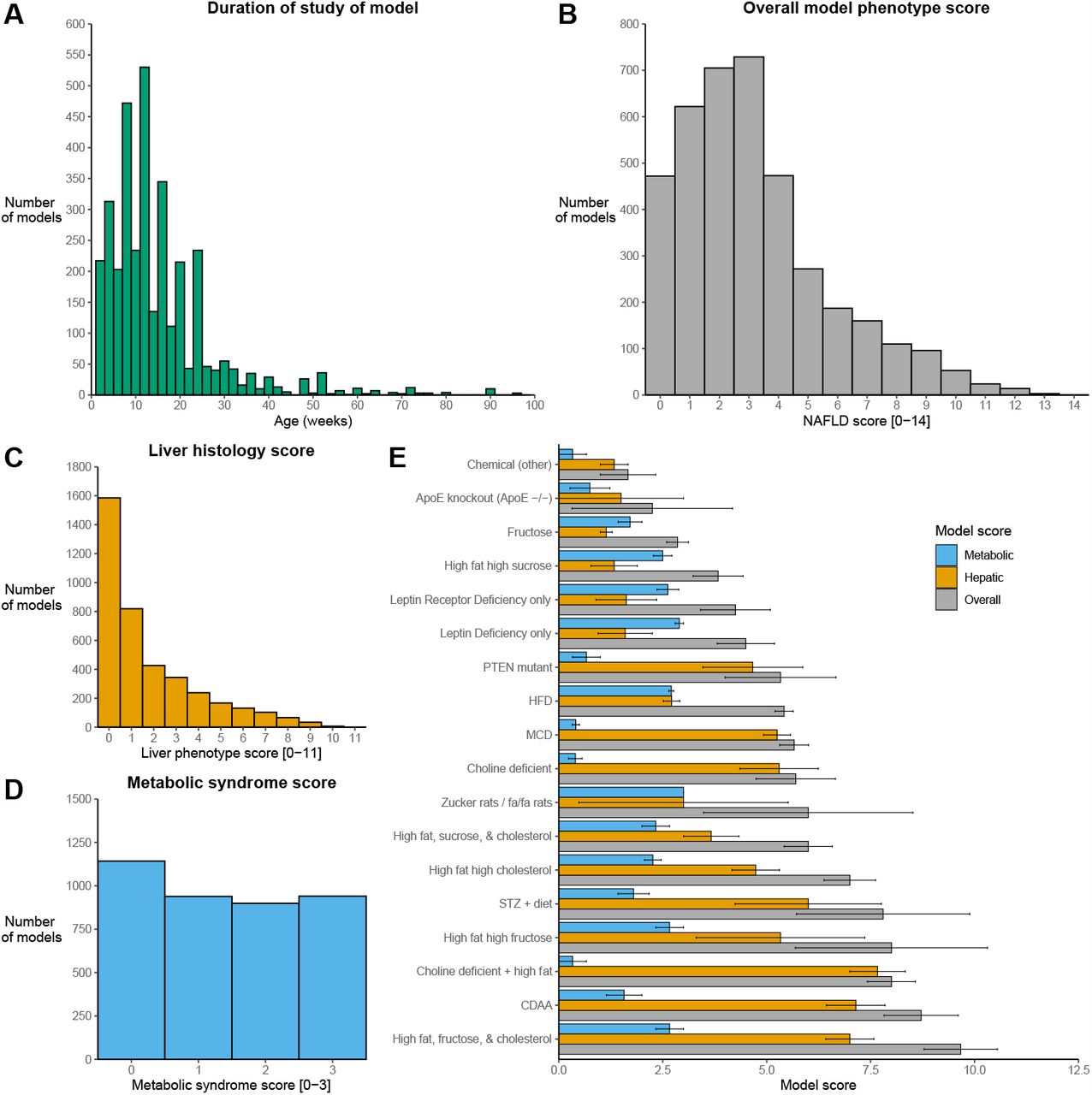

- How best to use results from mice or rats with fatty liver [see separate post]

Comparing fatty liver in children and adults

Children and adults with fatty liver are generally quite similar: more likely to be obese, more likely to be diabetic (or pre-diabetic), and more likely to have higher levels of fats in the blood. But there are a number of specialist differences, for example seen on samples taken from the liver (liver biopsy). Also, almost all the research done on fatty liver has been in adults (e.g. how long it takes to get cirrhosis from fatty liver). At the moment we assume that if you get fatty liver 10 years earlier (e.g. at 13-years old) then you’ll get cirrhosis 10 years earlier. But there isn’t much evidence to prove this yet.

For this reason, I have coordinated a network across Europe to study fatty liver in children. We have published our protocol and are still in the early phases. We have two peices of work that are still undergoing review by the scientific community about the genetics and blood fats of fatty liver in children. Overall, we hope we’ll be able to help answer some of the big questions about fatty liver in children.

Other work:

- Working with the team from Rome, we found that one kind of inflammation we see on liver biopsy is seen in children with more liver scarring. These children also seem to be more obese and more diabetic. This is very similar to what is seen in adults.

- Despite lots of good studies having been done, there is no single diet or drug that yet has strong evidence to be recommended for fatty liver in children. This was the case when we summarised the evidence in 2019, but the field does move quickly.

- There is a move away from ‘non-alcoholic’ fatty liver disease and towards ‘metabolic-associated’ fatty liver disease (‘MAFLD’). This emphasises the importance of obesity and diabetes in the condition. It also makes it clear that children can have fatty liver plus other conditions.

Understanding the genetics of fatty liver

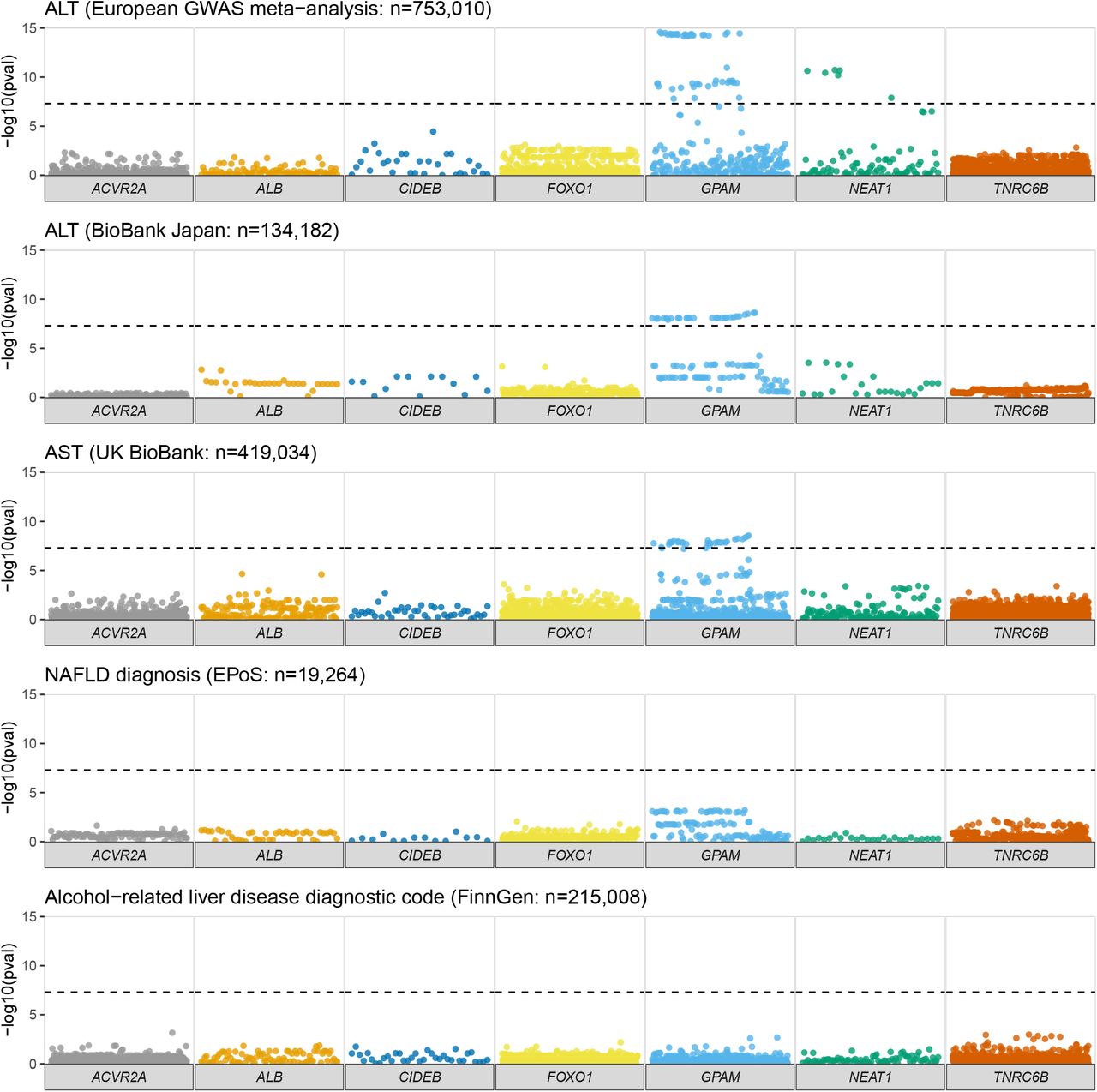

Our genes (made of DNA) influence lots of things, including height, hair colour, and risk of certain diseases. For fatty liver, like most other conditions, it is a combination of genes plus other factors that determine whether you are affected. I am interested in understanding which small (common) changes in DNA (‘variants’) are linked to fatty liver.

In 2020 I coordinated an international group of researchers to look whether one specific change near a gene called ‘MBOAT7’ was linked to fatty liver disease. Earlier research had suggested that it was but some studies didn’t find it to be linked. So we gathered all the data on the topic (a ‘meta-analysis’) and found that this variant near MBOAT7 does increase fatty liver disease. But it only has a very small effect, whilst there are other genes (and non-gene factors) that will have much bigger effects.

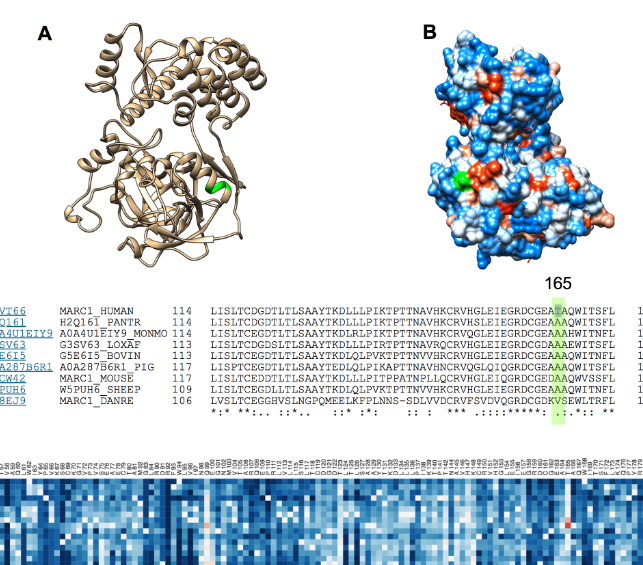

I have also done some work with the team in Cambridge to understand how some genes may influence fatty liver. There are 5 or 6 specific changes (‘variants’) in genes that are known to cause fatty liver. We looked at how these variants affected the metabolism of nearly 20,000 people using specialist blood tests. The results gave us a better knowledge of what these genes normally do in the liver.

Lastly, we all get mutations (harmful DNA variants) in our genes as we age. Some of these can related to cancer or cause diseases to be more severe. Other researchers have found that, in people with fatty iver, there are some genes that get more mutations in that we’d expect. I’ve analysed these genes and found they seem separate to the genes variants we inherit, which cause risk of developing fatty liver. But this study is still undergoing review by the scientific community.